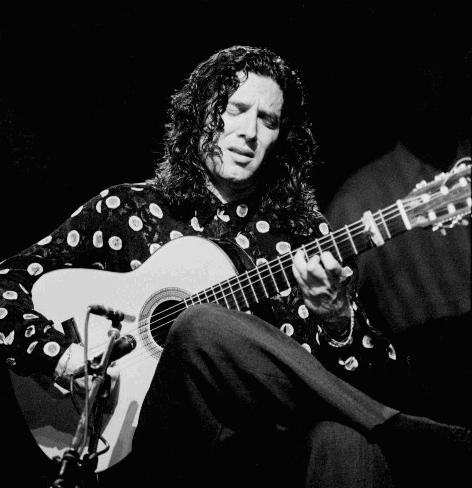

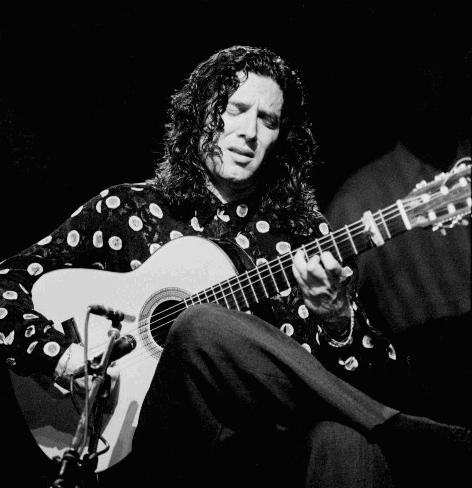

On Tuesday night April 1st a packed Paradiso breathes the atmosphere

of a family reunion. All over flamenco lovers meet and greet each other,

in joyous excitement on what is to come. No, apparently it's no April fools

joke, when Tomatito strolls onto the stage with his guitar. He receives

the cheers and applause from the audience with an almost apologizing nod.

It goes quiet when he starts to play. Fascinated the public gets carried

away by the music of one man and a guitar, and is whipped up by dizzying

bulerías. Tomatito smiles after every successful falseta, as if

the guitar surprises and enchants him as well.

Other artists announce themselves. Potito, who, at the early age of

20, is already a major player of the 'jovenes flamencos', sings without

much devotion before the interval, but comes to life in the second part

by the bulerías of the guitarist. Dancer Joselito Fernández

dances only once. Tomatito makes the show throughout. The crowd shouts

for more and then sees him - after a few more steps of bulerías

- disappear between the curtains.

Who is this guitar master? The facts are known: José Fernández Torres, born in Almería in 1958, inherited his nickname ‘little tomato’ from his grandfather, also guitarist, and father, director, who were both called Tomate. At an early age he was discovered by Paco de Lucía and was allowed to play on the records of Camarón de la Isla. When Paco de Lucía broke of the co-operation with Camarón, Tomatito continued. The duo was inseparable until Camaróns demise in 1992. Since then Tomatito has accompanied many artists, and made a name for himself as a solo guitarist, amongst other things with the CD's Barrio Negro (1991) and Guitarra Gitana (1996).

But how does he view the flamenco and his own role? To find this out,

we (your reporter assisted by guitarists Gerard Postma and José

Adame Sanchez) went to his hotel for an interview the next day. In any

case Tomatito doesn't have an attitude. Dressed in a black tracksuit he

walks unnoticed into the hotel and pleasantly takes the time to talk to

us. With the fiery performance of the previous evening still clear in my

mind, I ask him if he prefers to perform or record the records:

"Of course I prefer to play live. A CD is more professional, better

polished: here you stop, and you continue there .... The technique demands

that it should sound a certain way. You have to set the compás rhythm,

play in tune, combine this music with that. It's different. At a concert

there's the audience. Someone says something to you and you answer. Your

head works at top speed. There's no comparison of an audience that's yours

and that comes to see you. I will start touring Germany and I am sure that

the music will change somewhat from day to day. One day I'll stop here,

the next I'll continue there. That's flamenco, isn't it?"

He has great admiration for his former teacher Paco de Lucía:

"He is the greatest of all of us and he's the boss." As opposed to De Lucía,

Tomatito doesn't experiment with other forms of music, like jazz and South

American. "I think that the flamenco guitar is rich enough in itself, the

way it sounds. I prefer to play basic things as well as I can and find

new things in that. I don't say: flamenco is like this and that, and that's

it. For me flamenco is an open kind of music, but always without losing

it's own identity."

The other man of consequence in his life was Camarón. Tomatito's

solo career is always been seen in connection with the demise of Camarón,

as if he stepped out of Camarón's shadow then. How does he

feel about that himself? Is it this simple?

"No, it's hard," he sight and his voice goes softer. "I was very content

and very happy with Camarón, all my life with him. If he hadn't

passed away, I would have been with him always. I wouldn't have become

a solo guitarist, because he's my idol. I prefer singing to the guitar,

because the voice is a natural instrument and the guitar is made. Let a

child play guitar eight hours a day and in ten years he'll be a virtuoso

and he can make a living of it. Not so for the voice. I can study it eight

hours every day, and still I'll never learn to sing. You've got it, or

you don't. I was content with Camarón, but after that I had to either

stand on the market, or force myself to go solo. And bit by bit I found

a way to continue and play my music."

Does Tomatito feel like a godfather for the jovenes flamencos, who

would love to record albums with him?

"Oh, if I can help with that which Camarón left me, the power

of my name as the guitarist that accompanied Camarón, then I will.

I think we have the task to continue flamenco. Yes, they are younger than

I, but I prefer to see myself as an older brother, not as a father, because

I haven't gotten to that yet.

He also offers help to young guitarists using by a training-video (which

was earlier discussed in aficionao). Gerard can't help but asking if he

realizes how difficult this video is. Tomatito smiles apologizing: "It's

a bit difficult for people who are studying. And if one of my falsetas

costs me a lot of work, then it might cost somebody else twice as much

work. But everything you like, you learn bit by bit. And then a video like

this can be a way to stimulate, without wrestling" - and he depicts an

overzealous guitarist playing from the screen like a madman - "I'm not

a teaching teacher. In Spain there's many people playing my music. For

them the video is a way to take it in, at home with bread and a glass of

wine" - and in illustration of this he sags.

He agrees with Gerard that flamenco in Spain is becoming a top sport.

"But athletes have to be born as well. In Spain there's guitarists and

artists. there's many guitarists, professional, competitive, that play

well. But there's also artists that don't run as much, but end up better.

Paco de Lucía is supposed to be faster that any, if he'd want to.

But that's not the issue. It's the heart. If you play really fast, you

can end up with noise and you can't hear a thing. But you have to tell

people a story. I belief that the guitar is a universal language, without

words. And all guitarists are equal, because all people, all countries,

all races have a heart and feel things their way. You have to study, listen

to flamenco, old and new, just like the rest of us, and that's how you

learn."

"Where does flamenco go in the future?" an Italian journalist wants

to know who has joined us. Tomatito answers very resolute: "I think that

flamenco will always remain in it's place. Because the new things that

come out, like Pata Negra, are very good and draw a crowd. But the people

who want to hear flamenco, will go - thanks to them - also to other places.

You have to look for the authentic style, you have to deepen the well to

where you can find water. Camarón drew a big crowd for flamenco.

He had something modern and such a beautiful voice, that appealed to all

kinds of people, also younger people, who thanks to him became acquainted

with historic singers like Terremoto and Manuel Torre. Flamenco cannot

go in other directions, because flamenco is flamenco. Even Paco de Lucía

is more fond of his flamenco albums, than of those with Al di Meola. In

the end he prefers to play a seguiriya that sounds very flamenco, or a

beautiful taranta, than a South American rumba.

If flamenco loses its foundation, it's not flamenco anymore. And then

it will no longer appeal to the public. You love flamenco, because it sounds

flamenco. For example, in my music I can play a passage in a different

way, that you will say: it's nice, it's musically correct; a modern falseta,

fine, but the end is still: tateriámtateram! Get it?

Marlies Jansen

(English translation Carmen Morilla, 01 February, 1999)